This week in Charts:

Wages

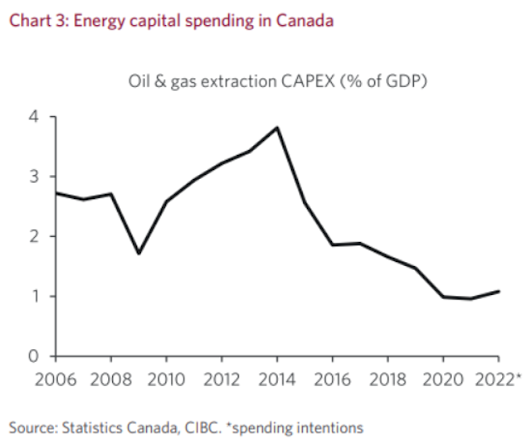

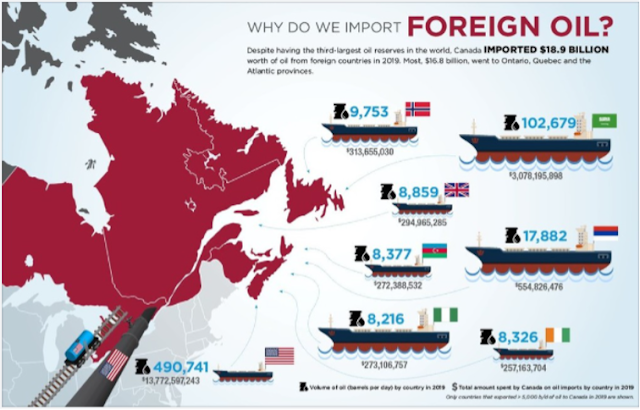

Oil

Buffett snubs Goldman bankers with quirky takeover price

Warren Buffett is telegraphing his disdain for Wall Street bankers with an oddball price on his latest multibillion-dollar takeover.

The US$848.02 for every share that Alleghany Corp. stockholders get from Berkshire Hathaway Inc. is the result of Buffett balking at the banking fee being set aside by the target company -- in this case for Goldman Sachs Group Inc., which is advising the insurer.

Berkshire had offered to pay US$850 a share with Buffett cautioning Alleghany that he didn’t want to foot the bill for the banking fees, according to a person with knowledge of the matter who asked not to be identified discussing private information. So any fee for a financial adviser would come out of the proceeds for Alleghany’s shareholders. The result is spelled out in a regulatory filing: an announced purchase price that subtracts roughly US$27 million for Goldman -- calling attention to Buffett’s stand.

The transaction is Berkshire’s largest since 2016, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. While deal prices typically reflect the back-and-forth between buyers and sellers, it gets smoothed over before the deal is struck. Most announcements are priced to avoid clunky numbers after both sides agree on a plan for how advisers are paid.

The Oracle of Omaha, known for his witty business aphorisms, rarely uses an investment bank with his deals, instead relying on Berkshire Vice Chairman Charlie Munger’s previous law firm, Munger, Tolles & Olson, to advise on acquisitions.

Howard Marks Memo: The Pendulum in International Affairs

At a recent meeting of the Brookfield Asset Management board, a discussion of Ukraine triggered an association with another aspect of international affairs – offshoring – which I first discussed in the memo Economic Reality (May 2016). Thus, the inspiration for this memo.

The first item on the agenda for Brookfield’s board meeting was, naturally, the tragic situation in Ukraine. We talked about the many facets of the problem, ranging from human to economic to military to geopolitical. In my view, energy is one of the aspects worth pondering. The desire to punish Russia for its unconscionable behavior is complicated enormously by Europe’s heavy dependence on Russia to meet its energy needs; Russia supplies roughly one-third of Europe’s oil, 45% of its imported gas, and nearly half its coal.

The other subject I focused on, offshoring, is quite different from Europe’s energy dependence. One of the major trends impacting the U.S. economy over the last year or so – and a factor receiving much of the blame for today’s inflation – relates to our global supply chains, the weaknesses of which have recently been on display. Thus, many companies are seeking to shorten their supply lines and make them more dependable, primarily by bringing production back on shore.

Over recent decades, as we all know, many industries moved a significant percentage of their production offshore – primarily to Asia – bringing down costs by utilizing cheaper labor. This process boosted economic growth in the emerging nations where the work was done, increased savings and competitiveness for manufacturers and importers, and provided low-priced goods to consumers. But the supply-chain disruption that resulted from the Covid-19 pandemic, combined with the shutdown of much of the world’s productive capacity, has shown the downside of that trend, as supply has been unable to keep pace with elevated demand in our highly stimulated economy.

At first glance, these two items – Europe’s energy dependence and supply-chain disruption – may seem to have little in common other than the fact that they both involve international considerations. But I think juxtaposing them is informative . . . and worthy of a memo.

Canada's nuclear industry ‘blindsided’ after exclusion from green bond framework

Many in Canada’s nuclear industry have been left questioning the federal government’s commitment to the technology after nuclear power was excluded from the first ever Canadian-dollar-denominated green bond.

The Green Bond Framework, introduced in March, lays the groundwork for a targeted inaugural issuance of C$5 billion for the 2021-22 period and will mobilize capital in support of the government's climate and environmental objectives, the Government of Canada says.

The global drive to cut green house gas emissions, with over 130 countries pledging to reach net-zero by 2050, has prompted investors to earmark entire portfolios worth hundreds of billions of dollars into companies and projects that claim clean energy practices.

The definition of which practices can be included in such portfolios, granting them access to a rapidly expanding source of financing, has been the focus of intense debate, not least over differing opinions on the green credentials of nuclear power.

In Canada, items that were specifically excluded in the country’s new green taxonomy are the manufacturing of arms, alcohol or tobacco, gambling, fossil fuels and, to the outrage of many in the industry, nuclear power.

“We have been, quite frankly, blindsided by the release of the green bond because there was no consultation with the nuclear, or any, industry,” says President and CEO of the Canadian Nuclear Association (CAN) John Gorman.

This week’s fun finds:

The Proven Path to Doing Unique and Meaningful Work

It’s not the work, It’s the re-work.

Average college students learn ideas once. The best college students re-learn ideas over and over. Average employees write emails once. Elite novelists re-write chapters again and again. Average fitness enthusiasts mindlessly follow the same workout routine each week. The best athletes actively critique each repetition and constantly improve their technique. It is the revision that matters most.

To continue the bus metaphor, the photographers who get off the bus after a few stops and then hop on a new bus line are still doing work the whole time. They are putting in their 10,000 hours. What they are not doing, however, is re-work. They are so busy jumping from line to line in the hopes of finding a route nobody has ridden before that they don't invest the time to re-work their old ideas. And this, as The Helsinki Bus Station Theory makes clear, is the key to producing something unique and wonderful.

By staying on the bus, you give yourself time to re-work and revise until you produce something unique, inspiring, and great. It’s only by staying on board that mastery reveals itself. Show up enough times to get the average ideas out of the way and every now and then genius will reveal itself.

Malcolm Gladwell's book Outliers popularized The 10,000 Hour Rule, which states that it takes 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to become an expert in a particular field. I think what we often miss is that deliberate practice is revision. If you're not paying close enough attention to revise, then you're not being deliberate.

A lot of people put in 10,000 hours. Very few people put in 10,000 hours of revision. The only way to do that is to stay on the bus.

The Munger Operating System: How to Live a Life That Really Works

In 2007, Charlie Munger gave the commencement address at USC Law School, opening his speech by saying, “Well, no doubt many of you are wondering why the speaker is so old. Well, the answer is obvious: He hasn’t died yet.”

Fortunately for us, Munger has kept on ticking. The commencement speech is an excellent response to the Big Question: How do we live a life that really works? It has so many of Munger’s core ideas that we think the speech represents the Munger Operating System for life.

• Acquiring wisdom is a moral duty as well as a practical one.

And there’s a corollary to that proposition which is very important. It means that you’re hooked for lifetime learning, and without lifetime learning you people are not going to do very well. You are not going to get very far in life based on what you already know. You’re going to advance in life by what you’re going to learn after you leave here…if civilization can progress only when it invents the method of invention, you can progress only when you learn the method of learning.

• Learn to think through problems backwards as well as forward.

The way complex adaptive systems work and the way mental constructs work, problems frequently get easier and I would even say usually are easier to solve if you turn around in reverse. In other words if you want to help India, the question you should ask is not “how can I help India?”, you think “what’s doing the worst damage in India? What would automatically do the worst damage and how do I avoid it?” You’d think they are logically the same thing, but they’re not. Those of you who have mastered algebra know that inversion frequently will solve problems which nothing else will solve. And in life, unless you’re more gifted than Einstein, inversion will help you solve problems that you can’t solve in other ways.

• Learn to maintain your objectivity, especially when it’s hardest.