The inimitable charm of government bonds over the last 30 years or so has been their wonderful tendency to give capital gains when the world starts to fall apart. The fly in the ointment is that those capital gains came from an expectation that the Federal Reserve would reduce interest rates to combat any economic weakness Today that is probably no longer true. And while you can argue as to whether I’m merely speculating about a hypothetical future problem, let’s look at what happened to the 10-year bonds in each of the G-10 markets during the Covid-19 crisis this winter.

Those markets where short rates were meaningfully above zero saw significant gains in their 10-year bond, even if none were quite as impressive as we saw in the U.S. Those markets where the short rate was already around zero or lower, though, told a very different story. The average bond return in those markets was -1.3% and none of them had a positive return in the period. So much for hedging the losses in the rest of the portfolio!

And today, the group of countries where short rates are already around zero or lower consists of every member of the G-10, the U.S. included. As a result, it seems to me unlikely that any government bond in the G-10 would provide meaningful positive returns if the global economy should encounter further problems associated with the Covid-19 outbreak or for any other reason in the near future. If short rates and bond yields rise meaningfully between now and that future downturn, that might no longer be the case. But if you are counting on such a rise occurring before the next downturn, you are also counting on bonds delivering a negative return in the interim.

Long Bonds Are Bringing Trouble

Nothing new here, but it looks like a bad month for investment-grade in August has some managers and their clients taking notice.

“U.S. companies are locking in low yields now for as long as they can, and the result is pain for investors.

So far this year companies ranging from snack food maker Mondelez International to airplane manufacturer Boeing to communications giant AT&T have sold more than $290 billion of bonds maturing in 30 or more years, more than twice the longer-term securities sold over the same period last year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The average tenor of new issues this year is 12.9 years, up by more than a year from 2019, according to JPMorgan Chase strategists

Investors are buying longer-term notes to get higher yields in a near-zero-interest-rate world. But they’re also taking on more interest-rate risk in the process. Investment-grade notes posted a loss of 1.4% in August, the worst monthly returns since March and only the third negative month in the last two years, driven in large part by rising Treasury yields hitting longer-term securities.”

“Money managers who focus carefully on credit risk might have to pay more attention to the risk of longer-term yields rising, said Matt Brill, head of U.S. investment-grade credit at Invesco.”

Longer-term notes may offer yields that look high relative to the alternative, but they are still low on an absolute basis. The notes Mondelez sold this week that mature in 2050 paid a coupon of 2.625%, compared with 1.5% for the 10-year notes.

“For our total return clients on the insurance side, it’s hard to invest in these low, all-in yields, so more client dollars are going to different asset classes,” said Travis King, co-head of investment grade credit at Voya Investment Management in Atlanta.

By Max Reyes

Source: Bloomberg LP.

Here is an article from 1999 where a record number of U.S companies attempted to capitalize on market euphoria by splitting their shares. During the dot-com craze, investors responded very positively to stock splits, bidding share prices up even further, and stoking the eye-popping run-ups in the U.S. stock market. Qualcomm for example announced a 2-for-1 split in May 1999 and then a 4-for-1 split in November 1999. By December 25th the stock was up 1500% for the year.

Today, Tesla’s stock split investor reaction is somewhat ‘1999ish’. Tesla shares ran up 13% in a single day on just the announced stock split earlier in August.

Stock splits add zero liquidity or additional tangible value to investors but nonetheless broadcast a bullish message that resonates powerfully with investors. They often open the gates to more buyers by lowering the price of a company’s share. This makes them more attractive to more investors because more people are more likely to buy more.

In Malcolm Gladwell’s latest book, Talking to Strangers, he writes about the concept of alcohol myopia. It’s a theory that alcohol causes drinkers to focus on their immediate environment. As Wikipedia puts it, intoxicated individuals act rashly, choose overly simple solutions to complex problems and act without considering the consequences.

What does this have to do with investing? Well, right now it feels like we’re experiencing market myopia. Investors are focused on today, leaving the future for later. I’m not so much referring to the strength of the stock market, but rather all the stuff that’s going on around it.

Here are some signs that investors are getting intoxicated:

Extrapolating current demand

Companies that did well during the lockdown are generally expected to keep growing and profiting in the post-pandemic world, including home improvement stocks such as Home Depot Inc., Lowe’s Cos. Inc. and Best Buy Co. Inc., athleisure stocks like Lululemon Athletica Inc. and Nike Inc., and, of course, technology stocks.

Worrying about profits later

One of the features of this market cycle has been the emergence of what I call the “non-profit” sector: companies that are growing rapidly, but don’t have a clear path to profitability. Some of today’s tech giants weren’t overly profitable in their early days either (for example, Facebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.), but the next generation (Netflix Inc., Uber Technologies Inc., Zoom Video Communications Inc., Slack Technologies Inc. and Wayfair Inc.) appear to be different. They are mature companies and are losing money in a favourable business environment.

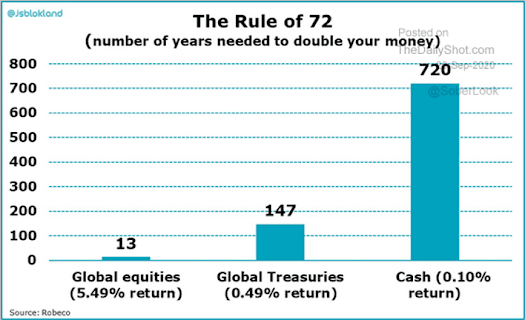

Chasing yield

The bonds of cyclical and highly indebted companies got hammered during the March meltdown as holders worried about getting their money back. Since then, however, most of the lost ground has been made up, even though the economic outlook is no more certain. Investors are moving up the risk scale to feed their insatiable appetite for yield, because high-quality corporate and government bonds are yielding next to nothing. Investors are getting a little more yield with a lot more risk.

Stock splits and price targets

In recent weeks, Tesla Inc. and Apple Inc. were sharply up on news that they were splitting their stocks. The splits made the shares more accessible to smaller investors but didn’t create one dollar of additional value.

Crowded trades and fat pitches

We can’t be sure how or when the hysteria will end. We just know it will. The most enduring inefficiency in the stock market is time frame. There will always be rewards for looking beyond the near-term noise to the opportunities and risks further out. The myopic market has put the spotlight on a select number of popular trades, which leaves plenty of other areas to explore. There are fat pitches out there, to use Warren Buffett’s analogy, they just haven’t gone viral yet.