This week in charts

The inverse weight of the Energy sector in the S&P 500 is the best and most consistent explanation of the market's P/E.

Will the election result be a catalyst to change the composition of the S&P 500?

1% out of “Growth and Defense” sectors equates to over 3% increase in Cyclical sectors!

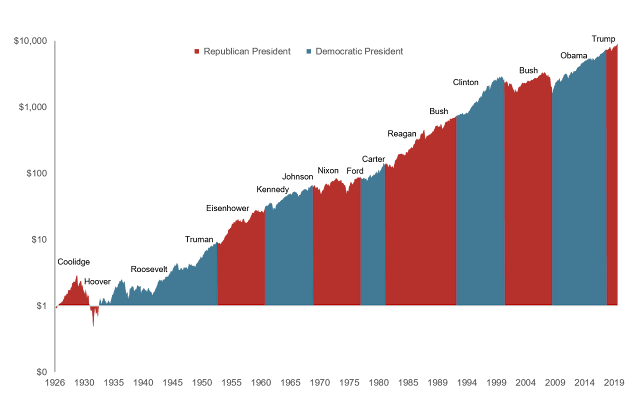

Historically, volatility in the stock market is elevated in the months leading up to an election. This is logical, as the markets hate uncertainty. For investors, it’s important to step back, put personal feelings about politics aside, and objectively assess the situation and what it might mean for your personal finances.

Stock market performance leading up to an election has also been a major indicator of the outcome. The performance of the S&P 500 in the three months before votes are cast has predicted 87% of elections since 1928 and 100% since 1984. When returns were positive, the incumbent party wins. If the index suffered losses in the three-month window, the incumbent loses.

Tonight, we leave the party like it’s 1999

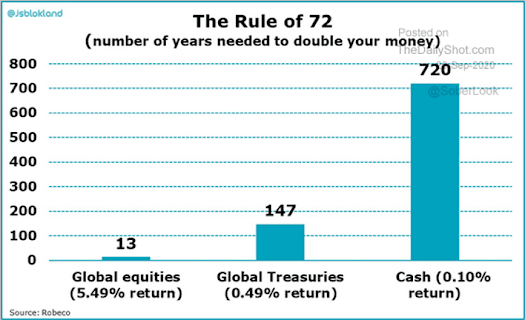

Today, U.S. stock valuations are at ridiculous levels against a backdrop of a global pandemic and global recession. U.S. Treasury bonds – typically a reliable counterweight to risky equities in a market sell-off – are the most expensive they’ve been in U.S. history, and very unlikely to provide the hedge that investors have relied upon.

This is the perfect time to look unconventional, just like in 1999. At today’s valuation spreads, the opportunity set is actually even better. And for those portfolios that are essentially benchmark-agnostic, we believe the opportunity set is the best we’ve seen in our working careers.

In 2020, the economy was destroyed by Covid-19; unemployment went from historic lows to historic highs in a matter of weeks. That should have reasonably dampened the market’s optimistic mood. But it didn’t (after the initial shock of March). The current valuation of the S&P 500 is actually higher than it was pre-Covid-19, which is dangerously odd given the sheer amount of uncertainty that exists (e.g., the shape of the economic recovery, the availability and efficacy of a vaccine, the risk of a second wave, U.S. citizens not adopting safety protocols, just to name a few).

The real worrisome signs, however, are the increasing silly behaviors of a speculative market. Exhibit 7 is a prime example of the aggressive trading activity of retail investors.

Though relatively calm for over a decade, this past spring awakened their animal spirits: daily trading activity increased nearly seven-fold over three short months. Bankrupted Hertz rallied 896% in May even though its own management team and the SEC said the company was likely worthless. Nikola, an electric truck maker with no actual earnings, no actual revenue, and…it’s true….no actual manufacturing facility to even make trucks, rallied 692% from April to early June. And then there was Tesla, which was bid up to $400 billion in market cap, making it more valuable than 12 established car companies, combined. The “You just don’t get it, GMO” taunts, the justifications, the mental gymnastics, the outrageous growth assumptions one needs to make to rationalize prices…it is all just too eerily reminiscent of 1999.

Americans have saved an extra $1.3 trillion since the pandemic

If household savings had grown in line with the recent pre-pandemic trend, Americans would have socked away about $2.2 trillion since the start of 2019. Instead, cumulative savings over that time period are worth just over $3.5 trillion. The difference—about $1.3 trillion—could pay for 9% of all the consumer spending that happened in 2019.

This savings boom had two basic causes. First, Americans cut their consumption dramatically. Part of what happened was that the higher-income people who were most likely to keep their jobs while working at home were also the people most likely to slash their spending on virus-sensitive categories such as dinners out and trips to the dentist. They were effectively forced to save because it stopped being safe to go out. Meanwhile, companies borrowed aggressively to offset the decline in sales while the government borrowed to offset the decline in tax receipts and pay for additional unemployment and welfare benefits. The net effect was that consumption spending fell almost 20% in the first wave of the pandemic.

Below are the IEA’s projections for electricity’s share of final energy consumption if countries stay on their current course (“Stated Policies Scenario”) and if countries meet the Paris Agreement goals (“Sustainable Development Scenario”). Under both scenarios, electricity’s share grows, but even under the Paris Agreement scenario its share is only 31% of total energy consumption by 2040. Under the Stated Policies Scenario it grows from 20% today to 24% by 2040.

Upstream oil investment needed to meet future demand