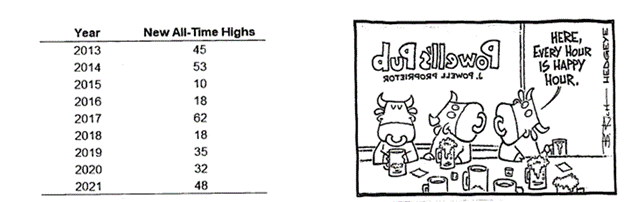

This week’s charts

Wage pressure

In the “hood”

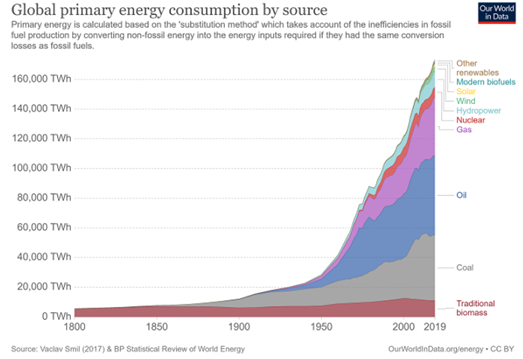

China’s steel mills must improve efficiency if they’re to cut their huge carbon emissions, say analysts

China’s steel mills can meet their goal of reducing carbon emissions if the industry is willing to accept the high cost of improving the efficiency of production, according to analysts.

As the largest crude steel producer and consumer, China’s steel accounts for about 15 per cent of the country’s carbon emissions and over 60 per cent of the global steel industry’s emissions. Steel companies in the country are under pressure now Beijing has fully committed to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050.

The largest steel producer in the world, Shanghai-based China Baowu Steel Group said it will reach carbon emission peak by 2023 and will reduce emissions by 30 per cent before 2035. The steel maker is also investing in innovative technologies to ramp up production. It has formed a five-year partnership with Anglo-Australian miner BHP to invest up to US$35 million in greenhouse gas emissions research, including the deployment of carbon capture and hydrogen injection in the blast furnace.

Innovative technologies have been developed and tested to eliminate the carbon footprint by using hydrogen or by capturing and storing the carbon during production. Still, the high costs have prevented the technologies being used on an industrial scale. Analysts said the situation would change in the future.

Ecosystem for failure

There has been a lot of cheerleading about do-it-yourself investing. People are opening discount brokerage accounts in record numbers and young investors are flooding into the market.

I can’t help but think we’re building an ecosystem for failure. The excitement isn’t about investing. It’s about gambling and speculation. About riding a one-way market that’s being fuelled by low interest rates and a complacency to risk.

To explain what I mean, let’s take a tour of the ecosystem, starting with discount brokers.

These firms are fighting for market share and their promotions are all about trading: low commissions, no commissions, 300 free trades a year and easy-to-trade apps. The visuals in the ads are powerful. A person who oozes success is looking at a screen with colourful charts and lots of numbers. Even I feel like I’m missing out on some really cool stuff, and I do this for a living.

The emergence of ETFs has brought the cost of investing down and made it possible to build well-diversified portfolios with just a few funds. But the industry doesn’t know when to stop.

There are more than 1,000 ETFs to choose from in Canada. There’s a fund for any mood you’re in. The initial emphasis on broad market exposure at a low cost has shifted to sector rotation (hard to get right), market timing (impossible to get right) and, yes, trading.

Option volumes have exploded for the same reason lottery tickets are popular — a small investment can pay off big. But there are no silver bullets in the options market. It’s dominated by professional traders and is highly efficient.

Today, investors have a cheering section rooting them on. Business news, apps and research websites like Motley Fool, and promoters on Reddit are telling you how to find the next Amazon and where the action is. Unfortunately, they’re selling the same edge to millions of others.

Investing is a solitary pursuit, not a social activity or entertainment.

We should not be too sanguine about a shrinking population

When my mother was born, there were fewer than 3bn people in the world. When I was born, there were almost 5bn, and when I gave birth to my daughter, there were 7.7bn. She may live to see the beginning of a new era: the point at which the number of people on the planet begins to decline.

The pandemic has caused a baby bust of historic proportions in some countries. In Spain, 20 per cent fewer babies were born in December 2020 than in the same month a year earlier, the lowest number since 1941, when such records began. Births fell 22 per cent in Italy and 13 per cent in France.

Almost half the global population now lives in a country or area where the lifetime fertility rate (the average number of babies per woman) sits below the “replacement rate” of 2.1 — the number that would keep the population stable. Even in sub-Saharan Africa, where the population is still growing fast, the fertility rate has declined from 6.8 in the 1970s to about 4.6.

Many will see this as good news for the planet. Rapid population growth has helped to put the environment under extreme stress. And in developing countries, declining fertility rates are usually connected to women gaining more education and opportunities.

That said, we shouldn’t celebrate declining fertility rates regardless of the cause. In some countries, people are having fewer babies than they say they want. In South Korea, where the fertility rate is now below 1, the working hours are too long, housing and education are too expensive and mothers too unsupported. Erin Hye-Won Kim, assistant professor at the University of Seoul, says the same system that powered the economy’s rapid development has put society under stress: “Working long and working late became virtuous.”

A stressed generation is not something to welcome, and it is not unique to South Korea, though it is particularly acute there. When the Financial Times surveyed young people around the world earlier this year, many spoke of a deep sense of insecurity that spanned unstable work and housing to the fear they would never be able to retire. Some said they didn’t feel secure enough to have children.

The risk is that, as countries begin to age and shrink, these dynamics enter a vicious circle, especially if young people see policy shaped increasingly around the needs of the more populous older generations.

We can’t control the number of babies women have, nor should we want to. But in many ways, having a child is an act of faith in the future. If some people are not having the babies they say they want, it is a warning sign we should heed, not something to shrug off because there are too many humans on the planet anyway.