Fourth quarter commentaries are now live!

This quarter Claire Thornhill takes us on a random walk that led to two big ideas ending up in the Global Portfolio, while Derek Skomorowski discusses the importance of dry powder – optionality and flexibility to aggressively pursue opportunities when the market presents them.

This week in charts

Manufacturing

Gender politics

GDP

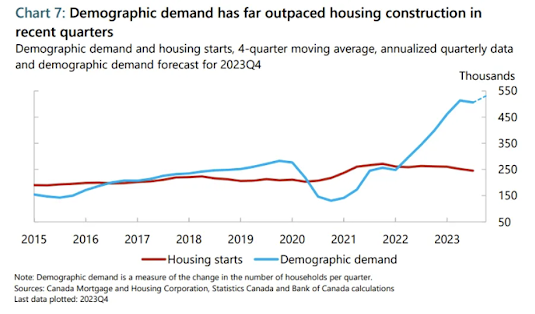

Housing

U.S. treasuries

Sectors

Equities

Why Americans Have Lost Faith in the Value of College

Arthur Levine, president emeritus of Columbia Teachers College and author of “The Great Upheaval: Higher Education’s Past, Present and Uncertain Future,” compares this moment in post-secondary education to the seismic change that followed the Industrial Revolution. That 19th-century wave of disruption washed over schools designed to meet the needs of a sectarian, agricultural society and transformed higher education into a sprawling system of community colleges, land-grant universities and graduate schools.

The dilemma faced by today’s high-school students is that while a similarly massive economic disruption has arrived, new educational alternatives have not. “Whatever comes next,” Levine says of Generation Z, “It’s not going to come soon enough for them.”

The digital revolution demanded a nimble realignment of the academy so that students could learn a quickly emerging set of skills to meet changing labor-market demands. Instead of adapting, campus interest groups protected their turf. Decisions reached by consensus usually meant the adoption of modest reforms that were the least objectionable to the greatest number of people, said Brian Rosenberg, former president of Macalester College and author of “‘Whatever It Is, I’m Against It’: Resistance to Change in Higher Education.”

As students abandoned the humanities and flooded fields like computer science, big data and engineering, schools failed to respond. The result was undersubscribed history and English departments and waiting lists for classes that led to well-paying jobs. New programs in emerging fields did not start because schools could not free up the resources.

The misalignment between universities and the labor market is compounded by the failure of many schools to teach students to think critically. Many students arrive poorly prepared for college-level work, and the universities themselves are ill-equipped to provide intensive classroom instruction.

A quarter of college graduates do not have basic skills in numeracy and one in five does not have basic skills in literacy, says Irwin Kirsch, who oversees large-scale assessments for ETS, the company that administers the SAT.

Quality control for college degrees falls to accreditors, but they approve programs at hundreds of schools that fail to produce financial value for graduates, and have kept many schools in business with a single-digit graduation rate. About one in 40 U.S. workers draws a paycheck from a college or university, and in recent decades the powerful higher-education lobby in Washington has quashed dozens of proposals to measure the sector’s successes and failures.

The pressure to place less emphasis on four-year degrees is growing, however. In what has been called the “degree reset,” the federal government and several states eliminated the degree requirements for many government jobs. Companies like IBM and the giant professional services firm Deloitte have too. Last year, a survey of 800 companies by Intelligent.com found that 45% intended to eliminate bachelor degree requirements for some positions in 2024. The Ad Council recently ran a campaign encouraging employers to get rid of the “paper ceiling.”

In place of a degree, some employers are adopting skills-based hiring, looking at what students know as opposed to what credential they hold. The problem is that the signal sent by a college degree still matters more, in most cases, than the demonstration of skills. The result is something of a stand-off between old and new ideas of job readiness. A LinkedIn study published last August found that between 2019 and 2022 there was a 36% increase in job postings that omitted degree requirements—but the actual number of jobs filled with candidates who did not have a degree was much smaller.

Ligaya Kelly worries her pet boarding facility on the outskirts of Los Angeles won’t survive the winter if loan costs keep rising. Economist Diana Mousina says she’ll have to sell her Sydney investment property if interest rates remain higher. John Stanyer has cut back plans for his holiday park in the north of England after his mortgage repayments almost tripled.

Like millions of borrowers across the world, the aspirations of Kelly, Mousina and Stanyer have collided with the steepest monetary tightening campaign in a generation. They’ve done what they can to weather the storm – Kelly has cut workers, Mousina dines at home these days and Stanyer’s expansion plans are on hold -- but how long they can hold out will depend on factors beyond their control, such as deglobalization, aging and the cost of the energy transition.

It’s arguably the biggest question in economics right now: Are these higher interest rates here to stay? In textbook jargon, it all comes down to R-Star (written as R* in economic models) -- the long-term neutral interest rate that keeps inflation steady at central bank’s preferred pace of around 2%.

In the decade or so after the 2008 financial crisis, the neutral rate dropped across developed economies as inflation remained generally subdued even as central banks kept interest rates at historically low levels. Deepening globalization meant cheap TVs and clothes, while memories of the crisis kept consumers subdued and held businesses back from investments, putting a lid on demand.

The post-Covid price spike shattered that calm, spurring a debate among economists, central bankers and bond traders about the future of inflation and interest rates – with very real implications for a world saddled with about $300 trillion in debt. If central banks conclude that R* is now higher, then they'll need to keep their benchmark rates more elevated too.

Anna Wong, chief U.S. economist for Bloomberg Economics, recently ran the numbers on what varying estimates of the neutral interest rate would mean for policy settings of the Federal Reserve, which meets later this week. She found a higher neutral rate would result in fewer interest-rate cuts in the next couple of years.

Some 2,300 miles east, at the austere Fed offices in Washington DC, officials aren’t ruling out more rates pain for Kelly and her kennel. In an August speech at the central bank's annual economic symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Chair Jerome Powell signaled that interest rates will likely stay high for some time, or even move higher, should inflation remain sticky.

Seared by the failure in analysis and communication that led to erroneous calls that inflation would prove transitory as prices spiked in 2021, Fed officials these days aren’t giving much away when it comes to their longer-term rates view. Powell has led officials in saying it’s too early to tell exactly where inflation and rates will settle once the economy normalizes.

Does China face a lost decade?

In a healthy economy, corporations use funds provided by households and other savers, ploughing the money into expanding their businesses. In post-bubble Japan, things looked different. Instead of raising funds, the corporate sector began to repay debts and accumulate financial claims of its own. Its traditional financial deficit turned to a chronic financial surplus. Corporate inhibition robbed the economy of much-needed demand and entrepreneurial vigour, condemning it to a deflationary decade or two.

So is China going the way of Japan? Chinese enterprises have accumulated even more debt, relative to the size of the country’s gdp, than Japan’s did in its bubble era. China’s house prices have begun to fall, damaging the balance-sheets of households and property firms. Credit growth has slowed sharply, despite cuts in interest rates. And flow-of-funds statistics show a narrowing in the financial deficit of China’s corporations in recent years. In Mr Koo’s judgment, China is already in a balance-sheet recession. Add to that a declining population and a hostile America and it is easy to be gloomy. Perhaps Japan is a best-case scenario.

Look closer, though, and the case is less conclusive. Much of the debt incurred by China’s corporations is owed by state-owned enterprises that will continue to borrow and spend, with the support of state-owned banks, if required by China’s policymakers. Among private enterprises, debt is concentrated on the books of property developers. They are reducing their liabilities and cutting back on investment in new housing projects. But in the face of falling property prices and weak housing sales, even developers with robust balance-sheets would be doing the same.

The end of China’s property boom has made households less wealthy. This is presumably breeding conservatism in their spending. It is also true that households have repaid mortgages early in recent months, contributing to the sharp slowdown in credit growth. But surveys show that households’ debts are low relative to their assets. Their mortgage prepayments are a rational response to changing interest rates, not a sign of balance-sheet stress. When interest rates fall in China, households cannot easily refinance their mortgages at the lower rates. It therefore makes sense for them to repay old, relatively expensive mortgages, even if that means redeeming investments that now offer lower yields.

What about the switch in corporate behaviour revealed by China’s flow-of-funds statistics, which show the corporate sector moving to a financial surplus? This narrowing is largely driven by the crackdown on shadow banks, point out Xiaoqing Pi and her colleagues at Bank of America. When financial institutions are excluded, the corporate sector is still demanding funds from the rest of the economy. Chinese businesses have not made the collectively self-defeating switch from maximising profits to minimising debts that condemned Japan to a deflationary decade.

Unfortunately, Chinese officials have so far been slow to react. The country’s budget deficit, broadly defined to include various kinds of local-government borrowing, has tightened this year, worsening the downturn. The central government has room to borrow more, but seems reluctant to do so, preferring to keep its powder dry. This is a mistake. If the government spends late, it will probably have to spend more. It is ironic that China risks slipping into a prolonged recession not because the private sector is intent on cleaning up its finances, but because the central government is unwilling to get its own balance-sheet dirty enough.

This week’s fun finds

The McDonald's McRib Is Coming Back. And That Could Boost Stocks.

Coincidentally, the McRib comes back on January 30.

The Ideal Vacation Length for Peak Relaxation, According to Experts

One piece of advice that is especially pertinent at the top of a new year of vacation planning: We should take several shorter vacations throughout the year instead of blowing all of our leave on one epic trip. According to such experts as [Breda University Researcher Ondrej] Mitas and [University of Groningen professor Jessica] de Bloom, the multi-vacation plan can keep your spirits up.

“We see relationships between frequency of vacation and happiness or well-being,” Mitas said. “So all else being equal, you should take more vacations.”

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, a professor of education, psychology and neuroscience at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, explained that most people are conditioned to operate in seven-day increments. For those of us who faithfully work weekdays, a week-long vacation feels appropriate and acceptable.

“We think in units, and a week is one of those units,” she said. “When you pick an eight-day vacation, you have replaced one unit of work with one unit of relaxation, plus a day to get there.”

When assembling trips for her clients, Denise Ambrusko-Maida, a travel adviser and founder of Travel Brilliant in Buffalo, focuses on the number five. She will recommend at least five days on the ground for trips that require no more than a day of travel on both ends. For long-haul trips, she suggests 10 days, plus travel days.

“If truly feeling like you’ve been on a vacation is important, then the five-day rule of not transiting is right,” she said. “And, depending on the trip, that can stretch out to more days if you’re moving from location to location.”

To make the most of your time away, tie up any loose ends before you depart. Immordino-Yang recommends a strategy often used to ensure restful sleep. She said to write down all of the projects and errands you need to complete before you leave.