Charlie Munger at the 2020 Daily Journal AGM (video)

Takeaways:

Many people automatically assume that because the market has been rising for many years that we must be in a bubble. This may be true but Charlie noted that each time period is unique, and rather than trying to pattern-match the current environment to some past analog, it’s important to think from first principles. Doing so leads me to proceed very cautiously given the prevailing optimism in the prices for most investments, but to also make investments when I do find those that meet my criteria for margin of safety.

Being able to recognize when you are wrong is a godsend. Charlie fights behavioral biases by consciously seeking out ways in which he could be wrong or looking for beliefs that he holds that are invalid. If he were to not do that intentionally, it’s very likely that his anchoring and confirmation biases would negatively impact his ability to think rationally.

100 Little Ideas that help explain how the world works:

Feedback Loops: Falling stock prices scare people, which causes them to sell, which makes prices fall, which scares more people, which causes more people to sell, and so on. Works both ways.

Reflexivity: When cause and effect are the same. People think Tesla will sell a lot of cars, so Tesla stock goes up, which lets Tesla raise a bunch of new capital, which helps Tesla sell a lot of cars.

False-Consensus Effect: Overestimating how widely held your own beliefs are, caused by the difficulty of imagining the experiences of other people.

Founder’s Syndrome: When a CEO is so emotionally invested in a company that they can’t effectively delegate decisions.

Skill Compensation: People who are exceptionally good at one thing tend to be exceptionally poor at another.

Ringelmann Effect: Members of a group become lazier as the size of their group increases. Based on the assumption that “someone else is probably taking care of that.”

Group Attribution Error: Incorrectly assuming that the views of a group member reflect those of the whole group.

Normalcy Bias: Underestimating the odds of disaster because it’s comforting to assume things will keep functioning the way they’ve always functioned.

Feedback Loops: Falling stock prices scare people, which causes them to sell, which makes prices fall, which scares more people, which causes more people to sell, and so on. Works both ways.

Reflexivity: When cause and effect are the same. People think Tesla will sell a lot of cars, so Tesla stock goes up, which lets Tesla raise a bunch of new capital, which helps Tesla sell a lot of cars.

False-Consensus Effect: Overestimating how widely held your own beliefs are, caused by the difficulty of imagining the experiences of other people.

Founder’s Syndrome: When a CEO is so emotionally invested in a company that they can’t effectively delegate decisions.

Skill Compensation: People who are exceptionally good at one thing tend to be exceptionally poor at another.

Ringelmann Effect: Members of a group become lazier as the size of their group increases. Based on the assumption that “someone else is probably taking care of that.”

Group Attribution Error: Incorrectly assuming that the views of a group member reflect those of the whole group.

Normalcy Bias: Underestimating the odds of disaster because it’s comforting to assume things will keep functioning the way they’ve always functioned.

How much does it cost to buy a fast-food franchise?

Many people dream of buying a fast-food franchise of their own, but few can afford it. All told, it might cost a franchisee upwards of $2 million to develop, build, and buy the right to open a McDonald’s or a KFC. Many chains won’t even look at your application unless you have a net worth of $1 million and $500k in readily spendable cash sitting around.

But there’s an exception to this: A franchise at Chick-fil-A — one of America’s oldest, largest, and most profitable chains — can be yours for just $10k.

Many people dream of buying a fast-food franchise of their own, but few can afford it. All told, it might cost a franchisee upwards of $2 million to develop, build, and buy the right to open a McDonald’s or a KFC. Many chains won’t even look at your application unless you have a net worth of $1 million and $500k in readily spendable cash sitting around.

But there’s an exception to this: A franchise at Chick-fil-A — one of America’s oldest, largest, and most profitable chains — can be yours for just $10k.

Why is opening a Chick-fil-A franchise so cheap? Chick-fil-A, not the franchisee, covers nearly the entire cost of opening each new restaurant. The franchisee only pays the $10k franchise fee. What’s the catch? In return for paying most of the upfront costs, Chick-fil-A takes a MUCH bigger piece of the pie (royalties). While a franchise like KFC takes 5% of sales, Chick-fil-A commands 15% of sales + 50% of any profit.

At $4.2m per store, Chick-fil-A’s average revenue is the highest of any fast-food chain in America.

Seems like a great deal if you can be accepted. With a 0.13% acceptance rate, it’s harder to become a Chick-fil-A franchisee than it is to get into Stanford University (4.8%), or get a job at Google (0.23%).

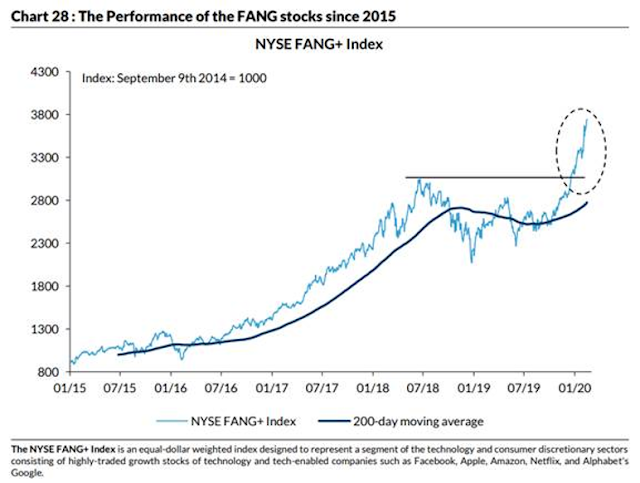

Charts of the week

This week's funnies.

At $4.2m per store, Chick-fil-A’s average revenue is the highest of any fast-food chain in America.

Seems like a great deal if you can be accepted. With a 0.13% acceptance rate, it’s harder to become a Chick-fil-A franchisee than it is to get into Stanford University (4.8%), or get a job at Google (0.23%).

Charts of the week

This week's funnies.