Matilde, partner since 2010 (Toronto, ON)

Downtowns

IPOs

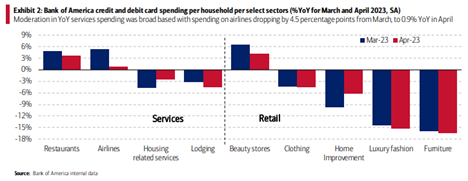

Household spending

Makers of food and household staples are pushing deeper into dollar stores because the low-cost retailers are opening thousands of locations each year. They are adding fresh produce and attracting shoppers squeezed by inflation, giving manufacturers with slumping sales a chance to grow. "It used to be, you would get odds and ends" liquidated from other retailers' unsold inventories, said Ed Johnson, a principal with Deloitte Consulting LLP focused on retail and consumer products.

Now, makers of pantry staples are treating dollar chains with the same rigor as Walmart due to their size and scale, Johnson said. A study by Tufts University found the low-cost stores, which number well over 35,000 in the U.S., are the fastest-growing U.S. food retailers by share of household spending - though Dollar Tree stopped selling eggs.

Executives at packaged food companies like Conagra Brands Inc. say the stores are increasingly attractive because they are installing more freezers and refrigerators for items like budget TV dinners, breakfast sandwiches and yogurt.

"The main play is frozen vegetables," and frozen fruit, in dollar stores' expansion into private label food, said Jim Griffin, executive vice president at Daymon, a consulting firm that works with retailers on their store brands. "There's strong consumer acceptance."

Griffin added that dollar stores are also introducing more "premium" private label brands, like Dollar General's Nature's Menu for pets.

Most dollar stores - which are less than half the size of a Walmart location or most traditional grocery stores - only sell the fastest-selling, basic items because of limited shelf space. Crane said the metric dollar store executives watch the closest is "dollars per point of distribution" for individual products, which measures how much in sales each item generates over time.

New EV entries nibbling away at Tesla EV share

Throughout 2022, EVs have gained market share and consumer attention. In an environment where vehicle sales are limited by inventory and availability, EVs have gained 2.4 points of market share year over year in registration data compiled through September - reaching 5.2% of all light vehicle registrations - according to S&P Global Mobility data.

The nascent stage of market growth leaves others competing for volume at the lower end of the price spectrum. New EVs from Hyundai, Kia and Volkswagen have joined Ford's Mustang Mach-E, Chevrolet Bolt (EV and EUV) and Nissan Leaf in the mainstream brand space. Meanwhile, luxury EVs from Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Audi, Polestar, Lucid, and Rivian - as well as big-ticket items like the Ford F-150 Lightning, GMC Hummer, and Chevrolet Silverado EV - will plague Tesla at the high end of the market.

With the Model Y and Model 3 combined taking 56% of EV registrations, the other 46 vehicles are competing for scraps until EVs cross the chasm into mainstream appeal. (A recent S&P Global Mobility analysis showed the Heartland states have yet to embrace electric vehicles.)

"Evaluating EV market performance requires looking through a lower-volume lens than with traditional ICE products," Brinley said. "But growth prospects for EV products are strong, investment is massive and the regulatory environment in the US and globally suggests that these are the solution for the future." Production volumes today are restricted by factory capacity, the semiconductor shortage and other supply chain challenges, as well as consumer demand. But the issue of production capacity is being addressed, as automakers, battery manufacturers and suppliers pour billions into that side of the equation. Though there are many signals suggesting consumer demand is high and that more buyers may be willing to make the transition - and to do so faster than anticipated even a year ago.

But consumer willingness to evolve to electrification remains the largest wildcard. Looking past Model Y and Model 3, no single model has achieved registrations above 30,000 units through the first three quarters of 2022. The second-best-selling EV brand in the US is Ford. However, Mach-E registrations of about 27,800 units are about 8% of the volume Tesla has captured, according to S&P Global Mobility data.

While logic dictates that further growth will require more EVs being offered in the $25,000-$40,000 price range, the willingness of buyers to spend more today reflects an aspirational nature to the choice.

Tesla's EV-only strategy gives it a retention advantage - as few EV owners have returned to ICE powertrains. But as new EVs arrive, loyalty will be tested. Currently, the Model Y has a 60.5% -brand loyalty and had nearly 74% of buyers come from outside the brand (the conquest rate) - tops in the industry. Who is Tesla conquesting from? Toyota, Honda, BMW and Mercedes-Benz. Toyota and Honda are only beginning to get into the EV market, though have yet to enter the fray in earnest.

This week’s fun finds

What It Takes to See 10,000 Bird Species

I was sitting in the middle seat of a battered van snaking up switchbacks to the summit of Tinajas Valley, tires inches from the edge of steep drop-offs. Next to me was Peter Kaestner, one of the world’s most prolific birders. “I can see why I haven’t seen this bird before,” he said, speaking loudly as the van rumbled over dirt and rocks. “It’s not the kind of thing you’re gonna bump into.” Kaestner is tall, with friendly blue eyes, and gives off a smart approachability. (He jokes that when he was younger he resembled Robert Redford, but he knew that he’d hit a turning point in his life when people started comparing him to former Syrian president Hafez al-Assad.)

We were headed to a ridgetop to look for the elusive white-throated earthcreeper, a drab brown bird with a curved beak like a T. rex claw. The bird prefers steep-walled desert washes at specific elevations in the central Andes, and would be a “lifer” for Kaestner. Birders call the complete tally of all birds they’ve ever observed their “life list,” and each new species a lifer. A person who keeps track of their life list is a “lister,” and someone obsessed with listing on a global scale is a “big lister.” I’m a lister myself, though I spend more time researching birds than chasing them. For my PhD at the University of New Mexico, I studied hummingbird migration and speciation in the Andes. These days I work as a postdoc at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, which runs eBird, the go-to platform for scientists and hobbyists to record bird observations.

On eBird, Kaestner is ranked number one, and he wants to be the first person in the world to see 10,000 bird species. The 69-year-old’s life list is currently at 9,796. The couple hundred birds he still needs are some of the rarest and most difficult in the world to spot. They’re often found in places that are basically inaccessible, off-limits due to political unrest, or threatened by deforestation and climate change. But Kaestner’s quest to hit 10,000 is his personal Dawn Wall, an obsession he’s sustained over decades, and he will not stop until he reaches his goal—if even then.

Kaestner has taken a nontraditional path to reaching 10,000. The pursuit is often considered a rich person’s pastime, like climbing the Seven Summits: many obsessive listers and bird chasers take months or years off work, spend personal fortunes, retire to chase birds full-time, or turn to vanlife. Kaestner is an exception. He birded his way to about 9,500 while working for the Foreign Service for 36 years on a modest government salary. He and his wife, Kimberly, a diplomatic specialist, fought for tandem placements so they could work together overseas, and he often achieved his birding goals through creative scheduling.

While living in Kuala Lumpur, Kaestner left the house at 3 A.M. on Saturdays to drive more than two hours each way in search of the rusty-naped pitta, returning to the Malaysian city by noon to play with his young daughters. “It took me over two dozen trips to get that bird,” he says. “But I wanted to be home to spend the afternoon with my family.”

“He does go off on his birding trips where it’s just birding, but he always makes time for family,” says Kimberly. “He’s always been good that way.”

In 1986, Kaestner became the first person in the world to see a representative of every bird family in existence, 159 back then. But the birding event that most changed his life was his 1989 discovery of the Cundinamarca antpitta, a species new to science. Kaestner had traveled outside Bogotá, Colombia, for work and was exploring a forested area up a newly constructed road. Suddenly, he heard a call he didn’t recognize.

He recorded it, then played the call repeatedly to lure the bird in, waiting for over 45 minutes. At one point, the bird popped up and called behind him. He crawled through the undergrowth and reached a clearing. Then Kaestner saw it. It wasn’t a known Colombian bird, he was sure of it. But back then, the references he needed to verify whether it was a new bird for Colombia, or a new species entirely, didn’t exist. Upon returning to Bogotá, he confirmed that it was a species previously unknown to science; it was formally described by biologists in 1992. His recordings and dictated field observations are now archived in the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library. For Kaestner, who has always been driven to contribute to the scientific record, the discovery was monumental. Antpittas remain his favorite birds.

High costs putting farming out of reach for young people, affecting all Canadians

The rising cost of land is making it harder than ever for young farmers to enter the business. And those barriers come at a time when a growing number of older farmers are planning to leave the industry. Organizations promoting farm succession worry that if young people are unable to enter the industry, only the largest companies will endure, reducing the diversity of crops and livestock and widening the gap between Canadians and their sources of food.

"The main challenge right now is really the cost of agricultural land," said Benoît Curé, co-ordinator of ARTERRE, a program that pairs aspiring farmers with landowners and farmers planning to retire.

Curé said multiple factors are contributing to rising prices, including real estate speculation — especially near Montreal suburbs — and strong competition for the best soil in a province where only around two per cent of the land is suitable for farming.

Last year, the price of agricultural land rose by 10 per cent, which isn't unusual, he said in a recent interview. "Over the last 10 years, we've had annual increases of about six to 10 per cent." The average dairy farm in Quebec is now valued at almost $5 million, he said, almost double what it was in 2011.

With 20 per cent down payments usually expected for farm purchases, "you have to almost be a millionaire before starting your agricultural business," Curé said. If young people can't afford to get into farming, then most rural communities risk being left with two or three large farms, he lamented.

Farming has always been a capital-intensive industry — with high costs for land, equipment and inputs — but prices across Canada have risen above the revenue that can be generated from that land, said Jean-Philippe Gervais, the chief economist of Farm Credit Canada, a Crown corporation that lends to farmers.

"The relationship between the price of the land and the revenue that can be expected from the land — that ratio is the highest we've ever seen," Gervais said in a recent interview. "So we're really at prices that are the highest we've ever seen, not just in absolute value in dollars per hectare, but also relative to what can be generated in income."

It's now rare for farmers to turn a profit from land they buy just by farming it, he said, adding that most farmers only make their money back when they sell. Large, established farms can fund the purchase of more land from the revenue generated on land that's already been paid for, he added.