This week in charts

U.S. employment

U.S. & Canada high rise construction activity

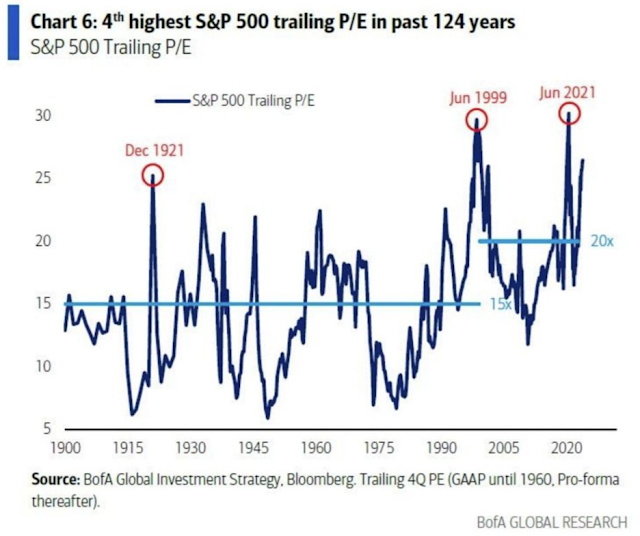

MSCI region valuations

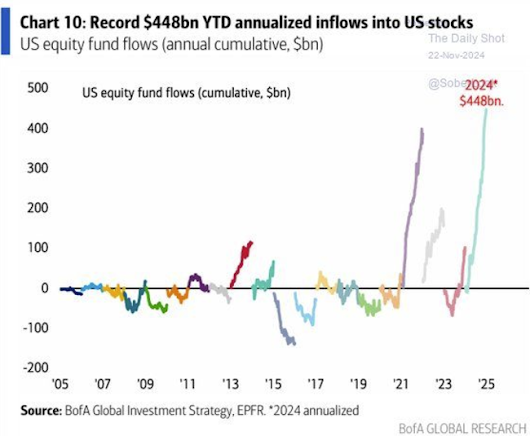

U.S. equity flows

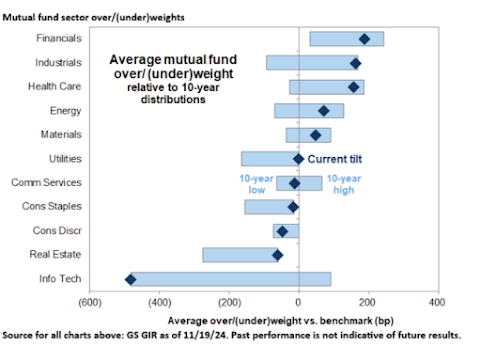

U.S. equity sector flows

Companies outperforming the S&P 500

Russell 2000 – Profitable vs non-profitable

Leveraged long ETFs

French stock market

U.S. power demand growth

Interest rates

U.S. government bonds

Global private equity

Tariffs are a misunderstood tool

If you want to understand the effects of tariffs on the economy, ask economic historians. Their views tend to be fairly nuanced, generally recognising that the history of tariffs is a varied one. Sometimes they are associated with higher economic growth and other times with lower.

For many economists, however, tariffs have become an ideological litmus test with little acknowledgment of these variations. Tariffs in advanced economies — and especially in the US — only matter, they argue, to the extent that they affect the prices of imported goods. For that reason, they are seen as always harmful to the economy because they always hurt consumers.

These economists are partially right about the effect of tariffs on consumption. That’s because tariffs, along with most other forms of trade intervention, are designed to lower the consumption share of GDP — the amount households consume of the total value of goods and services they produce.

This doesn’t mean however that tariffs necessarily reduce consumption. Like nearly all industrial and trade policies, they “work” by transferring income from one part of the economy to another — from net importers to net exporters, in this case. They do this by raising the price of imported goods, which in turn, raises the profits of domestic producers of those goods.

As all household consumers are net importers, while net exporters are producers of tradable goods, tariffs are in effect just a transfer from consumers to producers. They are both a tax on consumption and a subsidy to production.

So wouldn’t US tariffs — a tax on consumption — make American consumers worse off? Not necessarily. American households are not just consumers, as many economists would have you believe, but also producers. A subsidy to production should cause Americans to produce more, and the more they produce, the more they are able to consume.

Tariff policy is “successful”, in other words, if it raises domestic production by enough to pull consumption up with it — ie, if it causes Americans to consume more by producing even more. In that case American consumers are clearly better off, even as the share they consume of total domestic production declines. Of course, as production rises faster than consumption, this usually means that the trade deficit is declining.

On the other hand, tariff policy is a “failure” if it doesn’t cause a rise in domestic production, in which case tariffs reduce the consumption share of GDP mainly by causing consumption to fall. This would clearly make American consumers worse off.

If the US were to put tariffs on coffee, for example, these would likely prove a failure because Americans are unlikely to increase domestic coffee production except at a huge cost in other resources. As a result, domestic coffee production wouldn’t rise by enough to raise the total US production of goods and services.

If, on the other hand, the US was to put tariffs on electric vehicles, the relevant question is whether US manufacturers would be incentivised to increase domestic production of EVs by enough to raise the total American production of goods and services. If they are, American workers would benefit in the form of rising productivity. In turn, this would lead to wages rising by more than the initial price impact the tariffs had and American consumers would be better off.

This week’s fun find

EdgePoint has officially moved! Huge thanks to Adam, Diane, Teresa, Matilde and everyone who had a hand in creating this new, beautiful space that we can call home.

The commas that cost companies millions

How much can a misplaced comma cost you?

If you’re texting a loved one or dashing off an email to a colleague, the cost of misplacing a piece of punctuation will be – at worst – a red face and a minor mix-up.

But for some, contentious commas can be a path to the poor house.

.jpg)