This week in charts

U.S. mobile traffic

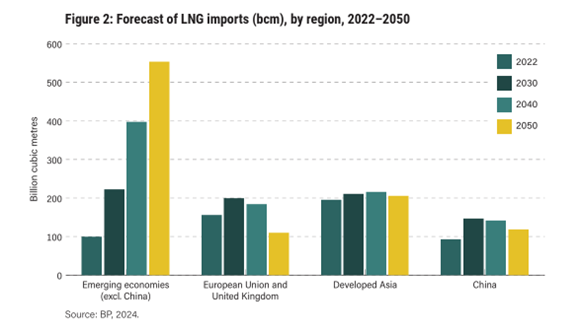

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) demand

LNG imports by region

Electrification

U.S. 10-year Treasury yield since 1790

Reserve currencies

Hedge fund net flows into Industrial stocks

Growth in total employment - Magnificent 7

U.S. and Euro area banks bond holdings - Share of total assets

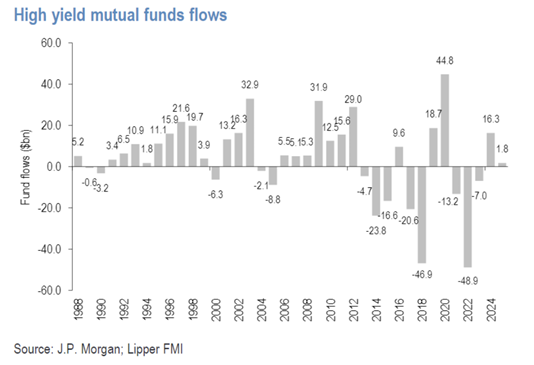

High-yield fund flows

Bond spreads

Average tariff rates

Researcher demographics

The Japanese government bond market is in trouble

The Japanese government bond market was already having a bit of a springtime nightmare, but a poor auction of 20-year debt earlier this week has sent long-end yields soaring to their highest levels ever.

|

The Japanese yield curve is upward sloping — in fact, the steepest yield curve in the developed world. That means longer maturity bonds should have higher yields. And yet, the 35-year JGB now yields over 100 bps more than the 40-year one, simply because it is less liquid and “off-the-run”. That kind of glitchy pricing is pretty stark evidence of the evaporating demand for longer-term Japanese debt.

Japan’s fiscal problems are well known, of course. The country has had a massive debt burden for many years. Its credit rating is three notches below the US even after the recent US downgrade. Prime minister Shigeru Ishiba called Japan’s fiscal position “worse than Greece’s” — presumably referring to the Greece of the European sovereign debt crisis (Greece is in OK shape right now). None of this is new.

But several things have changed recently.

First is inflation. Headline CPI in Japan is now 3.6 percent, and has been above 2 per cent for over three years. That means that a 30-year bond yield at 3.15 per cent is still below inflation, or negative in real terms.

Second, Japanese insurers have virtually stopped purchasing very long-term bonds, to satisfy new economic solvency ratios introduced recently.

Third, long-term fiscal concerns are rising. The US is pressuring Japan to spend 3 per cent of GDP on defence (from the current 1.6 per cent). The ruling coalition is considering a supplementary budget, while the opposition is pushing for a consumption tax cut. No one seems to be talking about less spending and raising more tax revenues.

Perhaps the most important change is from the Bank of Japan. The central bank still owns a staggering 50 per cent-plus of the Japanese government bond market. But with deflation now in the rear view, the BoJ has started quantitative tightening — allowing its existing bond holdings to slowly hit the market. And as this one massive buyer has become a net seller, Japanese bond yields are normalising — aka rising.

Global bond markets are clearly paying attention. US Treasuries shrugged off the Moody’s downgrade, but since Tuesday the 30-year US Treasury yield has risen almost 20bp — the highest level since the 2008 crisis — to well over 5 per cent after dismal auction yesterday. As a result, US mortgage rates are back above 7 per cent.

There has been no data to speak of, and the tax bill that just passed the House contained no new surprises for the market. The main driver of the US bond move seems to be what is happening 7,000 miles away in Tokyo. In fact, the long end of pretty much every major bond market is getting caned in a broad-based duration crash.

Japan bulls will point out that the last few weeks are not a repudiation of Japan Inc — and they’re right. No one is fleeing the yen, and the Nikkei is still up for the year in dollar terms. The economic impact is limited by the fact that most Japanese debt — mortgages, corporate debt, etc — is issued in shorter bonds.

But. . . Japanese policymakers are now at serious risk of losing control of the long end of the Japanese yield curve, absent imminent and forceful intervention. And if that happens, it’s bad news for everyone.

This week’s fun finds

Nothing brings people together more than great food and even better company culture. The moai hosted by TJ from the Trading team (with an assist from his better half Tiffany), was no exception. The sausages, schnitzel sandwiches and Detroit-style pizza was simple, satisfying and exactly what we needed to end the week.

The world’s longest train journey is epic — but nobody’s ever taken it

The mountains of northern Laos are beautiful, but tough to negotiate. By car, it can easily take 15 hours to drive the 373 miles (600 km) of winding roads that separate the capital Vientiane from the town of Boten on the Chinese border.

Since December 2021, there’s a far straighter, much faster alternative: the brand-new high-speed Laos-China Railway (LCR) measures just 257 miles (414 km) between Boten and Vientiane, and fast trains cover that distance in three and a half hours.

The line is a marvel of engineering: It includes no fewer than 75 tunnels, which make up 47% of its total length, and 167 bridges, accounting for a further 15%. By all accounts, the views — outside of those tunnels — are spectacular. But the LCR is more than a scenic extension of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. For train enthusiasts around the globe, it is the final piece of a much grander puzzle — for this stretch is also part of the longest possible train journey in the world.