The price of long-term outperformance

When it comes to meeting long-term financial goals, the sad reality is that many investors don’t get there. How they feel today influences the decisions that affect them in the years to come, and they often make avoidable, emotion-driven mistakes. The discomfort of being different from the crowd, watching their investments underperform or jumping on the latest "hot" market trend are among the pressures investors face regularly.

Humans evolved as herd animals, so departing from the safety of the crowd is fighting against an instinct ingrained over thousands of years.

However, while summoning rare emotional discipline is hard, it’s not impossible. First, having an advisor who keeps things in perspective is key to staying calm through difficult times. Second, finding an investment approach you can understand, believe in and commit to for the long term is also important. The road to compounding wealth isn’t smooth, so it helps to have a map that shows you the way.

This week in charts

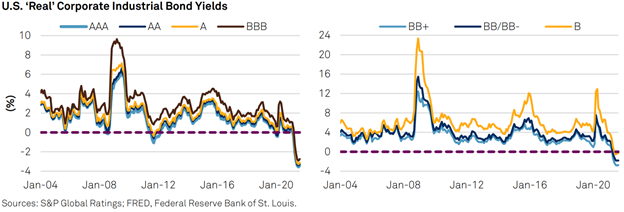

Lenders haven’t taken this much risk (or whatever the title I gave you was)

Axing the ESG buzzword

Some of Europe’s largest asset managers are starting to drop the once-ubiquitous ESG label from their company filings. They’re concerned that regulators will no longer tolerate vague descriptions of environmental, social and governance investing.

Europe’s landmark anti-greenwash rulebook is reining in an industry that ballooned to more than $35 trillion last year. The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) was enforced in March, but already in the lead-up to its arrival, European investment managers stripped the ESG label off $2 trillion in assets in anticipation of stricter rules.

Europe’s anti-greenwash rules contain some key sub-clauses that are forcing the asset management industry to substantiate their ESG claims. SFDR contains an Article 8 to define “light” green assets, and an Article 9 for “dark” green assets. The shade of green refers to the degree of importance accorded to ESG concerns. The EU is still working on more detailed descriptions of what the Articles may contain to stamp out any lingering mislabeling.

The adjustments sweeping through Europe’s asset management industry are beginning to make their way to the U.S., where ESG-labeled investment products this year surpassed those in Europe for the first time. Globally, ESG assets are on track to exceed $50 trillion by 2025, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

Individual investors choose options over stocks

According to CBOE (Chicago Board Options Exchange) Global Markets data, nine of the 10 most active call-options trading days in history have taken place in 2021. Options Clearing Corp.’s figures show that almost 39 million option contracts have changed hands on an average day this year, up 31% from 2020 and the highest level since the market’s inception in 1973.

So far this month, single-stock options with a notional value of roughly $6.9 trillion have changed hands, well above the $5.8 trillion in stocks that traded, according to Cboe data through September 22.

To date in 2021, the daily average notional value of traded single-stock options has exceeded $432 billion, compared with $404 billion of stocks, according to calculations by Cboe’s Henry Schwartz. Cboe’s data, which goes back to 2008, shows that this would be the first year on record that the value of options changing hands has surpassed that of stocks.

Shortage of workers in U.K.

BP Plc, the U.K.’s second-largest fuel retailer, said it’s shutting some of gas stations because of a nationwide truck driver shortage that’s threatening to derail the country’s economic recovery. Exxon Mobil Corp. also said that a “small number” of the 200 sites it operates for the supermarket Tesco Plc have been affected by the truck driver shortage.

The shortage of drivers and other workers hamstrung the U.K. food industry earlier this year, with stores running low on basics like milk and bread, tens of thousands of extra pigs piling up on farms, and retailers warning that there will be shortages of some products at Christmas.

The energy crisis has also ended up hammering the food industry. High gas prices last week forced fertilizer maker CF Industries Holding Inc. to close two plants that make carbon dioxide as a by-product. That posed an imminent threat to the food industry, which uses the gas to stun pigs and chickens for slaughter, as well as in packaging to extend shelf-life and the “dry ice” that keeps items frozen during delivery.

The death of profit

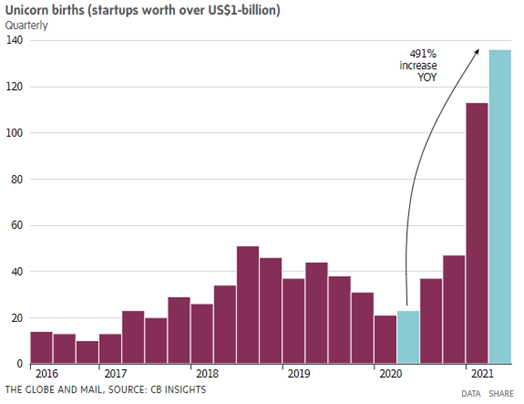

GFL Environmental Inc. went public in March 2020, and in the 18 months since, its share price on the Toronto Stock Exchange has almost doubled. The irony here is that GFL doesn’t make money. In fact, the company loses a lot of it. Over the past three fiscal years, GFL’s net losses have totaled $1.9-billion. It’s a common mindset lately. For all its hype, Uber Technologies Inc. has never made money – actually, it’s lost US$19-billion over the past five years. Streaming giant Spotify Technology SA has lost €2.6-billion ($3.8-billion) over the same period. There are now so many high-profile money-losers that Goldman Sachs recently created a Non-Profitable Technology Index, and its value soared when the pandemic hit.

“The amount of capital out there has made it acceptable to lose money for a longer period of time, in the hopes that eventually you tip the market and become a near monopolist, or at least a duopoly,” says Martin Kenney, a professor at the University of California, Davis.