This week in charts

S&P 500 Index drawdowns

Housing affordability

Canadian housing prices vs. income

Canadian exports to the U.S.

U.S. oil importers

China EV sales

Crypto funds

S&P 500 Index concentration

Magnificent 7

Entry price dictates returns

Not all European business is a profitless wasteland

Talk to European bosses about their continent and the responses are as varied as the languages they speak. Katastrophe, bark the Germans. The Italians wave their hands in exasperation. The French offer a resigned Gallic shrug. The British change the subject to the weather (which isn’t exactly fabulous, either). With governments collapsing centre-left (in Germany last month) and centre-right (in France on December 4th), plus war raging in next-door Ukraine, chaos is the political watchword.

European business can seem just as dysfunctional. In the past couple of weeks it has been a tale of bankruptcy (of Northvolt, a would-be battery champion), labour unrest (at Volkswagen, the continent’s biggest carmaker, where nearly 100,000 workers downed tools on December 3rd) and CEO defenestration (at Stellantis, a rival whose biggest shareholder, Exor, part-owns The Economist’s parent company). This week an activist investor ratcheted up pressure on Rio Tinto, the world’s second-most-valuable miner, to follow its bigger rival, BHP, in ditching its dual listing in London and settling for good in Australia.

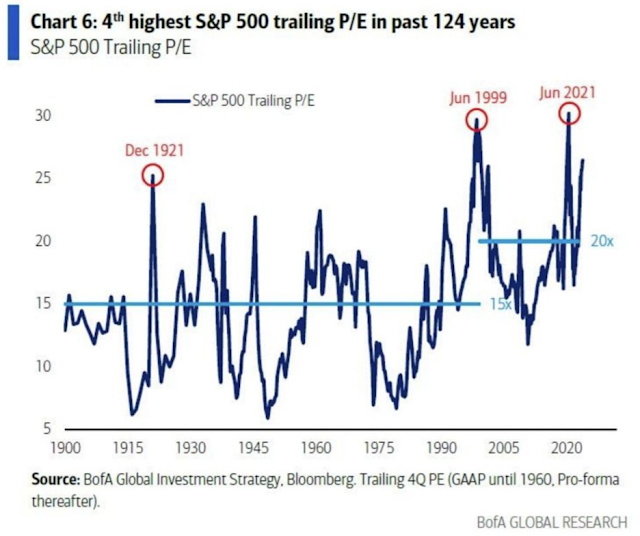

Add a dearth of success stories in artificial intelligence (AI) and no wonder Europe’s chief executives are in a dour mood, made dourer by smug American counterparts whose companies, on average, sell more, turn fatter profits and are valued more richly by markets. The entire STOXX 600 index of large European enterprises is worth a third less than America’s “magnificent seven” technology giants. Shares of firms in the S&P 500, its transatlantic equivalent, trade at 23 times future earnings, far above the 14 or so eked out by STOXX constituents.

Even excluding the AI-fuelled trillion-dollar outliers, investors regard American businesses as more promising than European ones. The price-to-earnings ratio of the 493 firms in the S&P 500 that are not Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia or Tesla is comfortably higher than for the STOXX 600. As a Spanish CEO might put it, ¿Qué diablos?

These jarring disparities in aggregates and averages are real and troubling. However, they may conceal as much as they illuminate. Closer inspection reveals pockets of European corporate strength, some more surprising than others.

In specific areas of commerce, Europeans outmatch even those self-satisfied Americans, sometimes handily. Europe’s drugmakers are collectively worth more than American ones and boast twice the return on capital. Novo Nordisk of Denmark launched Ozempic before Eli Lilly began selling its weight-loss drug. Europe lacks an Nvidia, but the $3.5trn AI-chip designer would not get far without ASML, a Dutch firm whose machines etch Nvidia’s blueprints onto silicon. Ryanair and other European airlines fly rings around American carriers in terms of profitability. And nobody does posh better than the French (think LVMH) and Italians (Ferrari, also controlled by Exor).

An alternative way to look for winners among European companies is to ask what factors might shorten the odds of success. Consider how much a business spends on research and development (R&D). In Europe, the keenest fifth of R&D spenders, a group that devotes at least 12.5% of sales to that end and includes those pharma giants and ASML, outperform less enthusiastic ones when it comes to return on capital. No such regularity is evident in America, perhaps because corporate R&D budgets there are generally higher relative to revenue to begin with.

European companies have two other things going for them. Many have patient shareholders, whose interests are aligned with businesses’ long-term success. For 237 of Europe’s 500 most valuable listed firms, at least 10% of stock is not freely traded (not counting state-controlled enterprises). Plenty of those stakes are in the hands of founders or, this being the old continent, their descendants. For America’s top 500 the equivalent figure is 90.

The other advantage is low expectations. Frothy American valuations may tumble, especially if AI fails to boost productivity in line with investors’ hopes. Sagging European ones could improve merely by reverting to the mean. Bon courage!

This week’s fund find

‘Brain rot’ named Oxford Word of the Year 2024

Our language experts created a shortlist of six words to reflect the moods and conversations that have helped shape the past year. After two weeks of public voting and widespread conversation, our experts came together to consider the public’s input, voting results, and our language data, before declaring ‘brain rot’ as the definitive Word of the Year for 2024.

Our experts noticed that ‘brain rot’ gained new prominence this year as a term used to capture concerns about the impact of consuming excessive amounts of low-quality online content, especially on social media. The term increased in usage frequency by 230% between 2023 and 2024.

.jpg)